Nature in global governance: Top-down and bottom-up approaches to adaptation

The world faces converging ecological and governance crises. As major biomes near collapse and inequalities grow, powerful nations prioritize short-term economic interests over climate and nature commitments. This article explores how outdated global governance structures exacerbate these pressures and why adaptive, equitable systems are essential to address the interconnected planetary emergency.

The planet faces a profound incongruity. On the one hand, a growing number of major biomes are approaching thresholds of ecological collapse under the pressure of myriad human factors. Increasingly strident voices from civil society, Indigenous and other groups are bearing witness to the lived experience of these crises. And on the other hand, the pull-back in climate, nature and social commitments, instead prioritising short-term economic growth interests by leading countries and corporate actors. This magnifies inequalities as ecosystem services, or benefits from nature, are most important to those with the least material wealth, so ecological collapse hits them hardest while they make the least contribution to global trends.

The multilateral global governance system, cobbled together in response to threats exposed by World War II, has shepherded this situation to the current state. After 80 years, the global governance system is fraying amid growing instability. This system bolstered the world order of the victors — Europe, the United States, Russia (the USSR), and an emerging China — first against a common enemy. After that enemy was defeated, they began competing for dominance amongst themselves. Over time, additional powers have emerged, wanting their seat at the table, and independent civil voices have also grown in strength.

Powerful countries that their own bio-capacities, have depleted or exceeded seek to preserve a global order through maintaining subsidies or importing natural resources from other, less powerful nations.

This plays out in the geo- and domestic political economies of post-colonial and economic dominance. Powerful countries that have depleted or exceeded their own bio-capacities, seek to preserve a global order through maintaining subsidies or importing natural resources from other, less powerful nations. Supplier countries and demographics, locked in unequal agreements have not been able to retain enough wealth. As a result, these countries cannot develop their own resources or strengthen their economies. This leaves them increasingly restless as they try to meet their own growing needs and claim their rights. Biodiversity loss in the global south is a symptom of a world order that is breaking under its own excesses, as are the other two aspects, pollution and climate change, in the triple planetary crisis.

This article explores how the ecological crisis is also a crisis of governance, and how adaptive governance, which embraces continuous learn-ing and responsivity, may best identify ways forward by linking coherently across scales from local to global. First, at global scales, geopolitical power relationships must adapt to new realities of today. Second, at local scales, both nature and people need to thrive, which also means adapting to climate change. Link-ages across these scales are addressed in the two reports adopted by the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) in December 2024: the Transformative Change Assessment and the Nexus Assessment[1], [2]. Critically, new global governance must shift what the Transformative Change Assessment called the underlying causes of the current condition – systems of domination over people and of nature, inequalities of wealth and power, and prioritisation of short-term material gain. This is necessary to rebalance the interlinkages between key elements of human lives, most pragmatically synthesised in the sustainability paradigm built on interactions between economy, society and our natural system (Figure 1).

1) Top-down, a new global order – power

It should not be a surprise that a world order designed 80 years ago is being shaken by current challenges. Importantly, there may be positive or negative outcomes from such disruption. A positive outcome would be that the inequalities of the old system are erased, with new and emerging powers across Africa, Asia, Latin America and ocean regions gaining their just share of power in multilateral contexts.

Further, the economic system did not recognise the value of nature, nor the rights of those that have stewarded it. Recognising the critical importance of natural capital and Earth system functions across all regions, and transforming the values driving decisions to be consistent with long-term sustainability and stewardship instead of exploitation, are essential founda-tions for lasting change. There is no doubt that equalising power relationships is a tall order, and resistance to change is demonstrably high. The increasing ferocity and damage of

anthropogenically-enhanced, or human-driven, disasters and proximity of multiple ecological collapses — for example, in coral reef, mountain and freshwater supply systems — have catastrophically high socio-economic consequences. These could serve as key triggers to motivate shifts away from top-down exercise of power, hopefully preemptively. Importantly, pathways to positive transformations can start from small shifts in views, practices and/or structures that reverse the current underlying causes. Therefore, initial shifts in any of these should be encouraged and accompanied by a strong commitment to go further, not stopping at comfortable but insufficient transitions.

2) Bottom-up, nature-based governance

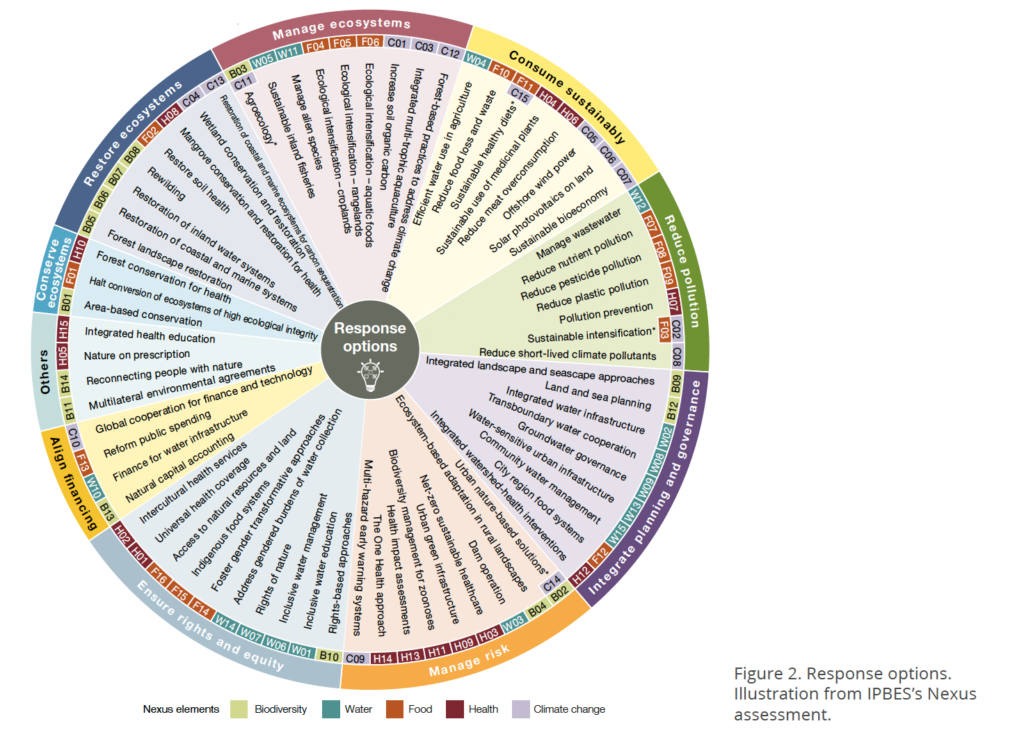

Recognition is rapidly growing regarding the scope and potential for localised, nature-based and adaptive solutions to emerging challenges. The Nexus Assessment addressed this and the complex and context-dependent feedbacks between five elements: two nature components, biodiversity and climate, and three economic sectors, food, water and health. The assessment synthesised over 70 solutions that demonstrate the potential to enhance co-benefits across sectors and reduce tradeoffs (Figure 2), while recognising nuanced customisation of individual contexts, and with success-es aggregating from local to larger scales. The assessment emphasised that a critical enabling factor of governance is that it is inclusive, holistic, equitable, cooperative and adaptive.

Focusing on meeting peoples’ needs from nature strengthens their direct experience and connection with the natural world, and thus fosters values of reciprocity and care that are essential for positive transformations[3]. Further, the Nexus Assessment showed how such connectivity with nature and solutions may emerge from any of the five elements it covered (Figure 2). By contrast, consider that IPBES recognises 18 different ways that nature benefits people. Nature-based solutions may emerge from any of the 18 categories, emphasising the immense diversity of adaptive responses that can deliver economic and societal value.

Acknowledging these diverse values will cer-tainly increase estimates of nature’s true value by orders of magnitude. Hopefully this will result in more investments, both financial and non-financial, that will protect and enhance nature and its benefits. Local adaptive approaches can help build collective action where actors work together in synergy, rather than in opposition.

Strategies to ensure that nature is healthy everywhere — so that it can provide what people need and sustain itself — can be applied consistently across diverse cultural, human and natural systems around the world[4]. Through a consistent framework, these adaptive approaches may scale up and work together to advance biodiversity, food, health, education, rights and other common goals as well as targets agreed multilaterally, such as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, Sustainable Development Goals.

Looking forward

The proliferating risks of ecological collapse and the breakdown of the multilateral order are interlinked consequences of a system unfit for 21st-century challenges. The current crises are direct consequences of limitations in the multilateral order. These crises strain the cur-rent system and can only offer poor respons-es, which creates a vicious cycle of decline.

Two primary risks may compromise positive outcomes emerging from the current crises:

a) holding on to the old multilateral order by continuing to patch the gaping holes enough to survive, but without shifting power relation-ships, and b) private-interest actors taking control, whether openly or covertly. In both cases, self-interest may help break down or bolster the old system, reinforcing existing power structures, benefit flows and inequalities.

This article has presented two complementary and necessarily linked adaptive governance approaches. Drawing from IPBES’s Transformative Change and Nexus assessments. The strategy is to leverage the breakdown of the current multilateral order to grow the seeds of positive outcomes — to give the best chance of the right top-down and bottom-up solutions to take root, grow and meet in the middle (Figure 1). Importantly, the approaches engage coalitions of actors linked across scales and geographies, and are facilitated by values that promote equity (see GCF’s Global Catastrophic Risks Report 2024 on ecological collapse). The mechanisms chosen to address global challenges in the coming years — across the major multilateral and other convening spaces — will provide early signs on whether a transformed new order is taking root and can be nurtured, or if business-as-usual responses will entrench existing interests.

The risk of multiple ecological collapses — both at regional and global scales — should be placed firmly at the centre of global govern-ance discourse. This risk is of greater existential importance than short-term economic or financial concerns. Prioritising ecological risks above economic interests is necessary to motivate adaptive responses needed to prevent ecological collapse.